Market Myopia — The Power Of The Dark Side

There is a broad body of theory that underpins our understanding of market behavior, especially financial markets — namely, that markets are rational. However, we believe there are times when markets, and, especially market players, become the victim of myopia, reflecting over-optimism, herd mentality and short-term thinking.

Many times, the lack of focus and inability to balance an understanding of how the dynamics of today’s markets fits into a broader, long-term perspective, including knowledge of historical cycles, creates key strategic points of inflections. The aftermath creates financial risks for some players and opportunities for others.

Midwest agriculture faces such a key strategic point of inflection, which will impact farmers and all suppliers to the farmgate, as well as the ag-retail/distribution system. In addition, an under-appreciation of these dynamics has significant strategic implications for companies’ business strategies and business models.

This article, the fifth in this series, focuses on our view that the key driver that will catalyze a major market reversal and secular downtrend in crop prices, profitability and farmland values is “The Power of the Dark Side.” Market myopia, in our view, has led players to under-appreciate the potential combined impact of three overlapping cycles on the global supply side dynamics for grains, especially corn.

The Power Of The Dark Side

There is no better example of the dynamics of the “Power of the Dark Side” than what has happened to the U.S. natural gas industry, which has gone from a shortage to a surplus in a little more than five years. The strategic point of inflection was driven by a quantum jump in natural gas prices to over $14/1,000 cubic feet (mcf), which created incentives to expand production and technological innovation (horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing). Shale gas has strategically altered the long-term natural gas supply outlook. This strategic transformation has driven prices down to below $5/mcf and the dramatic scale of new discoveries has resulted in the prospect of a long-term U.S. surplus.

Simply, the power of the supply side, reflecting “Economics 101” at work, suggests that Ag Bubble 2.0 could dramatically deflate. (See our article in the October 2011 issue of CropLife® entitled “Irrational Exuberance Or The New Normal.”)

Malthus And Halloween Day – History Creates Perspective

The under-appreciation of the power of supply side dynamics in agriculture goes back in history many centuries. However, the most notable was Thomas Malthus, who in his 1798 writings, “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” argued that humanity would be subject to long-term food shortages and starvation. His rationale was based on his view that human population increases geometrically, while food supply can only increase arithmetically, especially since farmland resources were finite.

More recently, during the last half of the 20th century, there were many dire predictions that humanity would not be able to feed itself. However, food production has increased more rapidly than population growth during that period, though malnutrition in parts of the world has been directly tied to impediments to food distribution.

And on Halloween Day 2011, significant media attention was paid to the United Nation’s estimate that the world’s population crossed seven billion people at the end of October 2011. Recognition of this threshold has reinforced the view that U.S. agriculture will “feed the world.”

The Power Of The Dark Side – Convergence Of Three Overlapping Cycles

From a U.S. perspective, the key driver of the “Power of the Dark Side” of agriculture’s supply side dynamics is the convergence of three cycles that will likely create significant U.S. and global upside supply surprises over both the short- and long-term.

The combined impact of the three cycles is expected to drive long-term supplies above long-term demand, creating intensifying downward price pressures, with continued price volatility fluctuating around the downward trend line. These dynamics will result in short- and long-term vulnerability to the current level of crop prices and profits, especially for corn, which will contribute to the deflation of farmland values. While prices over the intermediate-term will drive profits to breakeven levels for the average U.S. corn producer, efficient low cost producers will continue to generate significant profits.

Short-Term Cycle (One to Three Years) – Supply/Demand Deviation Cycles

Short-term ag commodity supply/demand cycles largely reflect short-term market deviations. Most notable is the impact of adverse weather on the supply side in major production or consumption areas. Short-term cycles can be also be generated by downstream market demand volatility, such as inter-crop market adjustments to short-term price changes, which temporarily alter normal usage patterns (i.e., current substitution of the wheat feeding of cattle, at the expense of corn).

These cycles are self-correcting in the short-term, as evidenced by the global wheat industry. In mid-2010, markets were caught off-guard from the adverse impacts of drought and fires on Russian and Ukrainian wheat supplies, which created a global supply shortage and a spike in prices. In just one year, the global wheat industry has found itself with excess supplies and dramatically lower prices, resulting from a global supply response to higher prices and a return to normal growing conditions in the affected areas.

Following two years of weather impacted corn yields in 2010 and 2011, U.S. corn production could rebound dramatically, based on a return to normal yields in 2012, unless the current continuation of the La Niña weather pattern results in another year of major yield reductions. Even if yields are significantly impacted by La Niña through the upcoming planting/growing season, the rebound in yields and supply will only be delayed until 2013.

Intermediate-Term Cycle (Five to 10-Plus Years) – Technology Innovation Cycles

Technology development and broad adoption has been a major driver of ag productivity in terms of yield gains, lowering costs, as well as expanding economically viable acreage. Greater use and the optimization of fertilizers, crop protection products, seeds with biotech traits, enhanced farm machinery/technology, and modern farm management practices will be continue to be major drivers of ag productivity, especially outside the U.S.

In the future, U.S. and global farm productivity gains are expected to be increasingly driven by the broader use of two major long-term technology innovation cycles: (1) biotechnology-driven enhanced breeding and additional trait development; and (2) precision technologies (use of integrated field specific agronomic information/technology/machinery).

Biotechnology-Derived Traits and Enhanced Breeding. While emphasis has been placed on biotech trait development, we believe agriculture is on the edge of broad-based yield gains and agronomic benefits from enhanced breeding, utilizing biotech derived tools and knowledge.

Agricultural productivity has benefitted from the widespread adoption of biotech traits, which has largely focused on herbicide tolerance and insect resistance traits. Biotech trait development continues to broaden to targets, such as abiotic stress (drought tolerance) and nitrogen utilization, which could have a substantial impact on accelerating yield gains, improving cost productivity, reducing risk and expanding acreage.

We believe significant advances in both offensive yield gains and defensive agronomic trait performance will be derived through enhanced breeding. Through the development of biotech-derived tools, combined with the progress in understanding plant genetics, farmers have started to see the field/economic benefits from the application of biotech-derived breeding technologies (marker assisted selection – combination of traditional genetics and molecular biology) to complex multi-genic agronomic traits in corn and other crops, resulting in both improved yield and defensive characteristics, such as disease resistance.

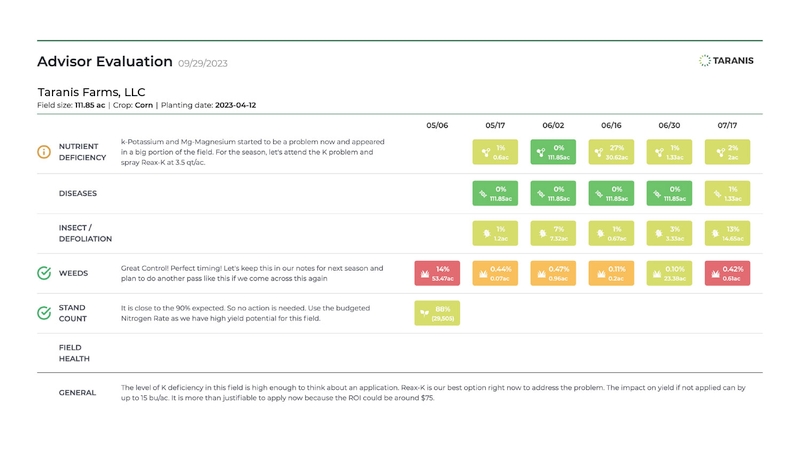

Precision Agriculture. Precision equipment (e.g., GPS and autoguidance) and precision services (e.g., fieldmapping and soil sampling) have been increasingly used to optimize soil/agronomic variability, input usage and field work, in order to enhance yield, cost productivity and profits.

A major disconnect that has limited effective use of these technologies is the rigorous quantification of the economic/financial benefit from the use of precision ag technologies/services in order to enhance decision making to improve yields and crop profitability. The precision ag industry is tackling this challenge, which will promote more aggressive adoption.

The key long-term challenge is the creation of a “holistic” approach that recognizes the interaction between plant genetics, soil chemistry, production management and information/technology/machinery systems. This integrated approach will result in improved yields, cost productivity, profits, risk management, and more consistent financial returns.

Long-Term Cycle (10-plus years) – Global Supply Cycle

The most significant global supply driver is the long term cycle reflecting accelerating global productivity gains outside the U.S, based on accelerating yield gains, improvements in cost productivity, and an expansion of global acreage. Two factors are of significance, in terms of future global supply growth: (1) potential for dramatic corn yield gains outside the U.S. In contrast to weather depressed estimated U.S. corn yields of 147 bushels per acre in 2011, non-U.S. yields are estimated at 65 bushels per acre; and (2) expanding acreage, especially outside the U.S.

It is estimated that average corn yields outside the U.S. increased by 2.4% per year over 2000-11, compared with 0.6% for the U.S. over the comparable period. (If U.S. corn yields in 2011 were normalized, on the order of 162 bushels per acre, the estimated yield growth rate would have been 1.5% per year from 2000-11.) Non-U.S. corn production has increased by 4.4% per year over 2000-2011, compared with a 2% annual gain (2.9% per year gain, weather adjusted) for the U.S. over the comparable period.

From a U.S. perspective, the greatest supply impacts will be driven by the short- and intermediate-term cycles, which will likely generate significant upside corn production increases relative to U.S. demand. In contrast, the most potent supply drivers outside the U.S. are the intermediate- and long-term cycles, which are expected to result in a dramatic acceleration in global production gains, especially for grains and corn.

Impact Of The Power Of Supply Side – Intensifying Competition

We believe the biggest surprises in the future will be dramatic increases in non-U.S. production. Dramatic production gains by many foreign countries will intensify competition with U.S. agriculture for export markets. A good example was the recently reported large Japanese purchase of corn from the Ukraine, at the expense of U.S. exports, since the U.S. has historically been the major corn supplier to Japan.

It is important to recognize that many of the key developing economies have emphasized the strategic importance of enhancing their “food security,” based on improving and expanding local production, as well as developing new business models to control new food supplies. A good example is China’s aggressive development of directly owned or co-owned large scale farming operations in Africa, countries from the former Soviet Union and South America.

We believe it would be very risky for U.S. agriculture to believe that it will “feed the world,” thereby creating a dramatic long-term sustainable increase in export demand to mirror expected production gains. While the U.S. has been a major exporter of corn, soybeans and wheat, which dominate Midwest agriculture, exports have been volatile due to production gains outside the U.S., as well as the dramatic volatility in the value of the U.S. dollar. It is more likely that U.S. agriculture will continue to maintain its position as the “supplier of last resort,” as evidenced during the 1970s, and more recently, over the past few years, when global supplies became short due to weather induced supply constrained short cycles.